Pwnplug

The Little White Box That Can Hack Your Network | Wired.com – the Pwnplug is a low-powered Linux computer loaded with hacking tool kits. The Pwnplug can crack wi-fi or power over ethernet connections in theory. It also illustrates the James Bond world that we live in, where the Pwnplug could look like anything, the only challenge being power. Bring your own technology poses additional challenges and would help conceal a Pwnplug. Also IT can’t dismantle or x-ray every every plug socket, phone charger, desk fan or extension lead in the building looking or a Pwnplug. Over time the components for a Pwnplug will get smaller and smaller

Beauty

L’Oreal: Educating Chinese Consumers Through Sports & Online Video | The China Observer

Consumer behaviour

New Study In Germany Finds Fears Of The Internet Are Much Higher Than Expected – Worldcrunch

Cheap and cheerful – downgrading by UK consumers

Beijing couples stay together for the sake of the house: law firm|WantChinaTimes.com

China accounts for one-third of world’s smokers|WantChinaTimes.com

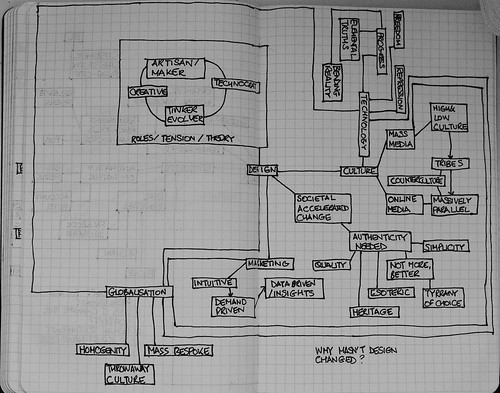

Design

Expandable formal dining table that seats ten and fits in a closet – really nice solution to a problem that most of us face. Interesting that Google’s Sketchup is used as a CAD file format

Economics

Productivity: When small isn’t beautiful | The Economist – emphasis on small businesses rather than growth businesses has crippled Europe

How to get a job in porn | The Next Great Generation – really interesting research on the economics of the adult entertainment industry

China’s economic growth ‘unsustainable’ – RTHK – according to World Bank president. Reflects the law of big numbers and China’s own refocus beyond GDP

Ethics

Microsoft v Google: How not to win friends and influence people | The Economist – someone needs to tell Frank X Shaw to let it alone, and one would have thought that Burson Marsteller would have known better with all the integrity guff they do when they wheel out Harold Burson

Why Are Harvard Graduates in the Mailroom? – NYTimes.com – anyone thinking about the equity of internships should read this article

Finance

Why the Fed Ignored Warnings and Let Banks Pay Shareholders Billions | Mother Jones

FMCG

Sugar Cane 洗护包-牛仔裤洗护包心水推荐“洗濯屋 仕上屋” ‹ CatWhy 潮流追踪 – interesting move by Sugar Cane jeans – detergent to keep your denim in tip-top shape, coming in both premium care and vintage wash look options

Starbucks Plots International Revival Through Local Campaigns

McDonald’s to Tout Quality in China – WSJ.com – taking brands back to their essence as a quality mark

How to

Google+ Hangouts get digital masks to enhance your next video chat | The Verge – really nice social object embedded into Google+ hangouts

Remove items from your Web History – Google Accounts Help

Hong Kong

What A Free And Hungry Hong Kong Press Looks Like From China – Worldcrunch

Ideas

REVEALED: How Giant Patent Troll Intellectual Ventures Does Business

Not a Film, Not a Game, But a Living Novel – transmedia storytelling

Innovation

NTT researchers develop breakthrough optical memory device

Vortex radio waves could boost wireless capacity “infinitely” | ExtremeTech

The energy race, featuring Bill Gates, Steven Chu, and Bill Clinton | The Oil and the Glory

The Pirate Scene Nimbly Adopts New x264 Video Codec | SiliconANGLE – innovation

Innovation and the Bell Labs Miracle – NYTimes.com

Sharp develops modules for digital signage players ‹ Japan Today – interesting that Sharp thinks that there is a market for PC-free controllers, a small move away from the general purpose computer

Ireland

Ireland Signs Controversial ‘Irish SOPA’ Into Law; Kicks Off New Censorship Regime | Techdirt – great reason why you shouldn’t invest in Ireland

Japan

Nissan May Revive Datsun – WSJ.com – brings back memories of the headmistress at my primary school who used to drive a Datsun Cherry 100a two-door in bright yellow (ironically this had sportier styling than the Coupé which looked more like a van from some angles)

GUCCI Official Japanese Language Blog – interesting that is showcasing traditional Japanese crafts

Korea

Seoul Food: Treating Your Idol to Lunch Is the True Test of Fandom – WSJ.com – fandom and Korean culture came up with a new cottage industry. The power of of Hallyu

Luxury

Shanghai Tang Hints At New Hong Kong Flagship With Facebook “Teaser” Contest « Jing Daily – I love how Shanghai Tang have made lemonade from the lemons they were dealt when Abercrombie and Fitch bid way too much money to get their store in the Pedder Building. Hong Kong retail property prices have gone insane

Issey Miyake Collaborates With Scientists On Origami Fashion Line [Pics] @PSFK

London’s White Cube Arrives in Hong Kong, Its First Outpost in Asia – WSJ

Marketing

How Microsoft is killing off the Zune and Windows Live brands in Windows 8 | The Verge

Media

Anonymous, Decentralized and Uncensored File-Sharing is Booming | TorrentFreak – In the long run this might drive more casual downloaders to legitimate alternatives, if these are available. Those who keep on sharing could move to smaller communities, darknets, and anonymous connections.

Update: Court Filings Suggest Google Fighting Feds Over Megaupload Emails | paidContent

Kim Dotcom’s first TV interview: ‘I’m no piracy king’ – 3 News

Michael Geist – Assessing ACTA: My Appearance Before the European Parliament INTA Workshop on ACTA

Labels And Spotify Still Struggle To Convince Some Artists On Stream Rates | paidContent:UK

Sony Music Boss: Censored YouTube Videos Cost Us Millions | TorrentFreak

Online

The truth about the iPad in Russia revealed | DaniWeb

How Three Germans Are Cloning the Web – Businessweek – Rocket Internet’s fast follower model which they deploy before American rivals can scale into markets

Facebook’s “Premium” – A User’s Nightmare? – what about the user context, is Facebook screwing itself over in the longer term with less engaged consumers

Japan Warns Google Over New Privacy Policy – on top of investigations in South Korea and US

I, Cringely » Yet another way China and Google are different – Google inflexibility compared to US stereotypes about China

So It’s the Kodak Patent Strategy for Yahoo Against Facebook – AllThingsD

Is it Really Full Steam Ahead for Facebook? « Sysomos Blog – really interesting post taking a good look at Facebook

Is the honeymoon over for Facebook gaming? — Tech News and Analysis

Retailing

Where to Buy Android Tablets Safely From China | gizchina.com

Security

Censorship is inseparable from surveillance | guardian.co.uk – or why the UK is digitally screwed

Social Network Login Status Detector Demo – really nice hack

I’m Being Followed: How Google—and 104 Other Companies—Are Tracking Me on the Web – The Atlantic

Wanted: Secure Android App Whitelisting – BYTE

Attack on Vatican Web Site Offers View of Hacker Group’s Tactics – NYTimes.com

GPS ‘spoofers’ could be used for high-frequency financial trading fraud (Wired UK) – GPS provides precise timing for time stamps on transactions

Are Twitter And Facebook A Serious Threat To Your Privacy? [INFOGRAPHIC] « AllTwitter – yes

Software

Steve Jobs was right: Dropbox is a feature, not a product | PandoDaily

Windows 8: Sugar coating on Microsoft’s hard-to-swallow tablet • The Register

Telecoms

S&P cuts Nokia rating to lowest step of investment grade – teetering just above junk status

Web of no web

HaptiMap project, FP7-ICT-224675 – really interesting project looking to integrate haptics and other stimuli into location-based services

Wii workouts unlikely to improve fitness • reghardware

Wireless

Pew: Smartphones overtake feature phones among adults in the U.S.