12 minutes estimated reading time

Online perfect market introduction

The train of thought on this blog post about online as a perfect market coalesced when I was re-reading Kevin Kelly’s New Rules for the New Economy for the first time in a decade. Kelly’s book built on the work done by fellow Wired contributor John Browning who pulled together The Encyclopedia of the New Economy which was published over a couple of issues of Wired magazine and as a compilation in a now out-of-print pamphlet that used to sold via the Wired web site.

What is the new economy?

Back in the 1990s when the internet started to move out research and academia into the commercial and consumer world lot’s of things were happening.

The cold war had finished, television viewers had seen CNN revolutionise coverage of the Gulf War conflict and the Iraqi army had been routed largely due to technology (and overwhelming firepower). Proto-reality show The Real World was fresh, with David ‘Puck’ Rainey becoming the first reality TV villain to capture the public’s imagination. The M in MTV still stood for music; but also stood for ‘much innovative programming’; Gap had some of the coolest ads on TV and the record industry was making money like music sales were going out of style.

Francis Fukuyama’s political philosophy tract The End of History (and the Last Man) seemed to catch the spirit of the time in terms of a utopian vision of the future, even if most of the people who name-dropped his work had never read it.

People realised that the internet would change things, just in the same way that mobile phones had started to change everyday life (punctuality suddenly became passé, when you could phone ahead give your excuses and have a much more fluid schedule). It was going to change lots of industries perhaps creating a ‘new economy’ of online businesses. From a cultural point-of-view the new economy and the information superhighway was something to hitch one’s utopian hopes to with echoes of Roosevelt’s New Deal some 60 years earlier.

The assumptions

The new economy was thought to bring about what economists would call a perfect market. Consumers would have information available at their finger tips and be able to compare the price of products throughout the world to get the best deal. There were even those who thought that consumers would have software agents to do this on their behalf and companies would have their power reduced by consumers. All of this change would be brought about by connected information and the rise of hobbyist communities who often knew more about a company’s products than the company themselves. This was seen to be a logical extension based on what people knew of the power of networks.

Consumer opportunities

Many of the early e-commerce businesses were arbitrage plays. Boxman had complex software from IBM that bought CDs from the cheapest distributors across Europe, shipped to its warehouse in Belgium and then shipped to consumers with some of arbitrage gained reflected in their discounted price. CD-WOW.com sold CDs from Hong Kong and other markets to UK consumers at prices that were up to 25 per cent cheaper than other suppliers. In the end, Boxman was brought down by poor software performance due to IBM learning about e-commerce as they went along and eventually CD-WOW had to pay £41 million pounds damages due to a prosecution brought by the BPI under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The ruling gave record companies a free hand to continue predation on UK consumers by supporting excessive prices on CDs compared to non-European markets. If it had been a bank instead of a record label, they would have been labeled loan sharks.

I worked on agencyside on the launch of a comparison shopping service called Dealtime UK (it re-branded to Shopping.com and is now part of eBay) which showed the price of CDs, consumer electronics shops and compared them across a swathe of retailers. Eventually search became a big part of the comparison shopping play with Google having its product search function and Yahoo! buying Kelkoo and tapping into that expertise to roll-out Yahoo! Shopping functionality across the international Yahoo! network.

Big Data

The demise of the dot com era saw changes in media consumption that went hand-in-hand with the roughly 30 per cent decline in online advertising spend bottoming out in 2002. Consumers started to find their way around the web in a different manner. Instead of having there homepage of their browser as a personalised melange of news, weather and horoscopes served up by a portal website like Yahoo!, Excite or MSN; there was instead a search box from Google, Baidu, Naver or Yandex depending where you lived in the world.

As search engines tried to provide better results, they realised that context was important and that a record of what searches people did may make some sense of it. This data is immensely powerful. An example of how powerful it is was show by the AOL Search debacle. In August 2006, an AOL Research project put three month’s worth of search data for 650,000 users online. The data had been anonymised, but that didn’t stop the New York Times tracking down Thelma Arnold based on her search data. At the time I worked at Yahoo! we were gathering as much data each day from consumers as would be held in the US Library of Congress two times over.

It wasn’t only search engines that had this inferred data inside it, other businesses like Amazon had been gathering information about consumer’s preferences towards different products. Netflix like AOL released anonymised consumer data into the public as part of a programme to crowd-source a better recommendation algorithm. Privacy concerns were raised following work done by the University of Texas and Netflix pulled the data set following an agreement with the FTC.

Web 2.0 impact on the perfect market

The web as a platform or web 2.0 came about out the ashes of the dot.com crash. The idea was that the web, had become a web of data that could be used through APIs to build new services and become more useful through mashing the data up. The key concepts that pioneers focused on was making the data usable and ensuring attribution of the data sets – (I’d recommend having a look at Tom Coates’ Native to a Web of Data presentation as a primer.)

One of the key things about this was that a number of the pioneers in this area like Flickr’s founder Stewart Butterfield said that APIs gave consumers power over their data, they could back up their images or take it elsewhere. Their content was exportable and market forces kept all the players honest and competitive.

However it could also be easily matched with existing data sets and much greater inferences derived from it.

Secondly, over time the moral imperative changed in these businesses. Facebook developed its site as being a digital equivalent of the Hotel California where you data can enter, but never leave. So as a marketer you have never had so much consumer information between the big data, inferred data and the ability of blending in further data to refine the knowledge further moves the needle from consumer to marketer in terms of economic power.

How could this be used to nullify a perfect market?

- Targeted advertising – based on understanding of the consumer behaviour, consumer spending power, life-state information. If you want to know the power of this information, look at how US supermarket Target wants to get hold of consumers as they are ready to start a family.

- Targeted offers – save your best offers for people who are most likely to act on them

- Dynamic cross-selling and up-selling opportunities – one of the biggest problems that we as marketers faced when I worked at MBNA a number of years ago was the irate consumers who would reach out when they had been offered a superior deal by us via mail. This need never happen again, instead inventory could be used to target them with additional services from a trusted brand

- Differentiated pricing – this is where things get interesting. For luxury brands you could deliberately use differentiated pricing as a barrier to the kind of consumers you don’t want. For insurance companies you could use a much wider set of data to make inferences about likely risks for everything from health to their likely driving-style

The trust issue

As the Edelman Trust Barometer has shown for the past decade or so trust is extremely important in consumer – organisation interactions and ongoing relationships and impacts on the perception of a perfect market. Or as Kelly puts it:

With the decreased importance of productivity, relationships and their allies become the main economic event.

He lists attributes of trust that shows how difficult it is to foster, and how fragile it can be to maintain:

Trust is a peculiar quality. It can’t be bought. It can’t be downloaded. It can’t be instant

So where does trust leave the information imbalance between consumers and the organisation that they interact with? It’s a big challenge, Kelly points out that for trust to work consumers have to know who has the knowledge and a full understanding of that they know. The problem is that organisations aren’t ready to have that adult conversation and full disclosure, particularly about what they can infer from the data that they have access to. The benefit that the consumer gets in relational activity is much less than what the organisation derives from that data. This would be especially true for someone like Facebook:

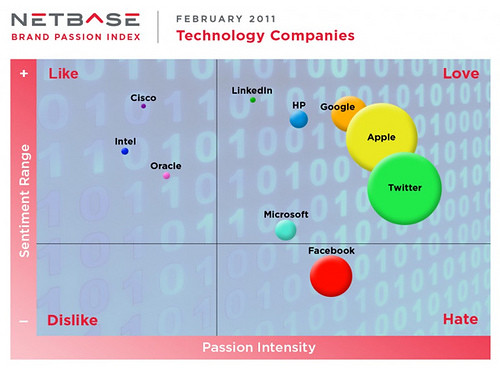

Netbase looked at how consumers relate to brands, it indicates that many people feel that they have to be on Facebook rather than they want to be indicating that the consumer benefit is low, so the corresponding trust they are prepared to put into the social network regarding their privacy is low.

Companies like Facebook and Path are treating privacy as an inconvenient hang-up of consumers that they must run an end game around rather than engendering trust. The less engagement these businesses have with their audience the lower the quality of the information and the consequent lower utility that they have for marketers. There is no perfect market in online advertising.

In the same way that consumers have a reduced trust in the media following incidents at organisations like News International; there is likely to be an inciting incident at some point between consumers and the online advertising eco-system that is likely to bring trust to a head. The perfect market knowledge advantage then becomes mute.

The internet becoming a too perfect market kills the golden goose being bad for consumers and bad for advertisers. The challenge is that the eco-system is a victim of its own success from 2002 to the end of 2011 the US online advertising market grew over four times to roughly 8 billion dollars a quarter. If someone steps back from the plate to take a more considered approach, someone else will rush in.

A prime example of this is the use of facial recognition software which even Google’s chairman Eric Schmidt agrees is a step too far, Facebook has already implemented it and Google has rolled it out as an opt-in feature on Google+. The problem with the opt-in is that Google doesn’t spell out to the consumer the full ramifications of the technology – yet it was obviously concerned at the highest level in order for Schmidt to go on record about it at a conference.

Looking at all this; it is counter-intuitive, but the market for consumer privacy should actually be with the brands that they are trying to engage them. How powerful would it be if a brand said: we can do all these things skulking around behind your back, pulling the strings but we aren’t going to and we don’t want to. We want to be a brand that you can address on your own terms.

The clock is ticking for the brand that will make that leap and the advertising eco-system that won’t. It was the Cluetrain Manifesto accused PR people of being afraid of their publics; were now in a situation where the online advertising eco-system is afraid of being completely honest with its audiences and afraid of their advertisers.

As Chuck D said:

The easiest and the hardest word to say is NO

More related content here.

More information

Here’s What Really Scares Eric Schmidt – Allthings D

Google+ Introduces Automatic Face Recognition To Photo Tagging (But It’s Completely Opt-In) – TechCrunch

Facial Recognition Technology: Facebook photo matching is just the start – PC World

Netflix Cancels Contest After Concerns Are Raised About Privacy – New York Times

CD Settlement forces prices up – BBC News

Tom Coates famous ‘Native to a web of data’ presentation that he gave at Future of Web Apps back in 2006 and Simon Willison’s write up of the presentation

How Companies Learn Your Secrets – NYTimes.com – How Target zeros in on consumers right around the birth of a child, when parents are exhausted and overwhelmed and their shopping patterns and brand loyalties are up for grabs

Where’s the Market for Online Privacy? | The Precursor Blog by Scott Cleland

Comments

One response to “Perfect market on internet?”