9 minutes estimated reading time

The luxury sector is undergoing a transformation, and nowhere is that more apparent than in the world of boutique e-tailers. I am of a generation that grew up with boutiques, carefully curated fashion looks from multiple brands.

Exclusive

As a child, my Mam would get me jumpers as I grew up from different small stores like this. To this day, the ultimate compliment she would give any item of clothing was that it was ‘exclusive’.

As I started buying my own clothes I pivoted between sports shops for my footwear, Ellis Brigham for layers, Caran D’Ache – a menswear boutique in Birkenhead at the time for jeans and ‘going out’ clothing. (Having known the owner/manager quite well, I suspect that the store was named after the Swiss writing instrument company, rather than the pseudonym of French satirist Emmanuel Poiré). This was where I got my first down jacket (by Naf Naf), Oshkosh B’gosh dungarees and Champion sweatshirts. At the time Ellis Brigham was a sea of Polartec and Gore-tex with no down jackets in sight.

I started venturing further afield and went to Quiggins in Liverpool, Affleck’s Palace in Manchester and what’s now the Victoria Quarter in Leeds. I’d also started coming down to London with friends to find brands I couldn’t get at home.

Famous high-end boutiques like Browns built a reputation for championing up and coming womenswear designers like Hussein Chalayan and Alexander McQueen. They also helped the likes of Ralph Lauren, Jil Sander and Calvin Klein start seeing in London. At their best boutiques moved culture as curators and taste makers. I got my love of American workwear from Caran D’Ache and Japanese streetwear from the late lamented Hideout which was just off Golden Square.

Department stores were the first aggregators of boutiques with a mix of single brand and multi-brand concessions under one roof. Brands like Selfridges, Harvey Nichols, Isetan, Lane Crawford, Mitsukoshi, Neiman Marcus, Saks Fifth Avenue, SEIBU and Shinsegae.

These established businesses have their place, indeed LVMH owns a number of selective retail businesses like DFS (often known as T Galleria), Le Bonne Marché and Starboard Cruises. So multi-brand distribution has a place in the luxury retail mix. Over time the premium department store brands and LVMH’s select retail brand would both have boutique e-tailers within their brands providing an omni-channel experience.

In the run up to COVID, multi-brand retail counted for 57 percent of luxury sales, management consultancy Bain expect this to decline to 36 percent of luxury sales by 2030.

Online

Online continues to disrupt retailing over a quarter century after it landed. The first casualties were book stores and music stores. Twenty years ago, one of the most enjoyable activities that I did in my spare time was rifling through record store shelves, digging for surprising or elusive vinyl records, CDs and DVDs.

Some of the places were I did this are long gone, like Tower Records in Piccadilly Circus. On the flipside, new businesses sprang up to be online first, or online only. Amazon started as a book store and eventually became the modern-day equivalent of the Sears Roebuck catalogue.

Luxury was no exception and a variety of dedicated boutique e-tailers sprang up:

- Matches

- MyTheresa

- Net-a-Porter

- YOOX

- Farfetch

In the same way that mobile operators were the key determinators of whether mobile phone shops were successful, luxury brands had the whip hand over multi-brand boutiques. Phones4U died when its relationships with EE and Vodafone came to an end. The FT article The implosion in luxury ecommerce implied a similar pivotal moment between Farfetch and Kering, but with Farfetch managing to sell itself to Korean e-tailing business Coupang instead of going into administration.

One brand / one store

Luxury brands have looked to gain more control over their customer experience and get closer to the customer overall. This has seen many brands open single brand stores. Up until the 1980s, Louis Vuitton sold mostly through department stores, now it’s mostly through its own brand channels. Some brands like Audemars Piaget, now only sell through their own single brand showrooms.

The big name department stores continued to hold a position in the marketplace due to their own brand power, even while smaller mid-market stores in provincial cities folded.

Over time, brands extended their shop front into the online sphere. This was done once two things were able to happen:

- An all-up online and offline view of a given customer and CRM systems allowed this to happen. This wasn’t for efficiency reasons to go online only, but to provide an omnichannel service to match customer’s omni-channel lifestyles.

- Getting this all-up view will also help with future EU legislation moving towards a circular economy.

- The ability to provide a high level delivery experience for online purchases. This mattered less with fragrances than it did with watches and handbags. High security logistics providers like Ferrari were able to provide this to the main luxury brands.

One small chink of hope for multi-brand stores is that single brand stores may be forced to either change business practices, or insulate themselves from legal action via authorised dealerships. A court case brought by two women against Hermés in the US claims that having to buy other products to get a crack at purchasing a Birkin bag is a violation of antitrust laws.

The obligation to buy other products first, is what the women claim is an ‘illegal tying arrangement’ which is why Hermés might be in violation of antitrust laws. Other brand who have authorised dealers rather than their own showrooms are less likely to be at risk.

Compressed middle-class

One of the first things that I learned when doing LVMH’s INSIDE LVMH certificate was that the bulk of luxury purchases are made by the middle classes.

Robert Gordon’s Rise and Decline of American Growth outlined how the middle classes in America (but also many other western countries). Income inequality, automation and globalisation drove a stagnation and decline in middle class numbers, even as the number wealthy increased.

Globalisation elevated a new middle class in Asian countries like Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Thailand. Energy drove middle class growth in the countries surrounding the Persian gulf and Nigeria. Louis Vuitton opened their first show rooms in the US in 1914, in Japan in 1978 (though department stores had been selling their products for years). The first Korean shop opened in 1984 and China eight years later.

Over the past few decades this was compensated by new middle classes growing. They don’t necessarily have the earning power of a middle class westerner, but the purchasing power level may vary considerably. So a middle class consumer in a country like Thailand, Malaysia or Singapore might have more disposable income than someone in the UK.

Japan’s middle class quickly reached stagnation due to the lost decades of economic growth after their 1989 asset bubble. Korea has gone through a similar challenge, it has seen raised consumption, but recently this is driven by household debt rather than prosperity.

China

Quantity is a quality of its own, which is a reason why Chinese consumers have been so important to luxury brands since the early 2000s when China joined the WTO and its economy took off. Once there was even a small growth in middle class numbers that represented a big increase in global luxury sector sales. The decline in economic growth due to the property sector bubble has dampened luxury sales to China. It is not only about the decline in ability to purchase, but also the decline in being seen to purchase western luxury goods.

This less conscious consumption started early on during the Xi administration’s desire to combat corruption and aspire to a more equal society. Gifting declined. Economic decline accelerated this Chinese macro-trend.

COVID and after

COVID changed consumption. Money that would have previously been spent on experiences such as restaurant meals or travel transferred into things. Both single brands and boutique e-tailers got a lift in this environment. But a wider economic effect is still working its way through the economy. This effect is known as the bullwhip or Forrester Effect.

This resulted in a number of economic distortions:

- Partial shutdown – Consumers no longer went to work or high traffic retail hotspots. Non-essential workers didn’t go to work. Logistics systems buckled under the weight of packages and luxury businesses diverted production to support medical needs such as LVMH’s perfumes businesses making hand sanitiser.

- Unusual increase in demand – Home working drove an increase in demand from media consumption and home improvement to buying more stuff from all that money they saved from not going out.

- Supply chain disruption – Air cargo prioritised medical supplies while existing stock sat in empty shops.

All of this disruption which drove inflation, this reduced demand as consumers had less to spend.

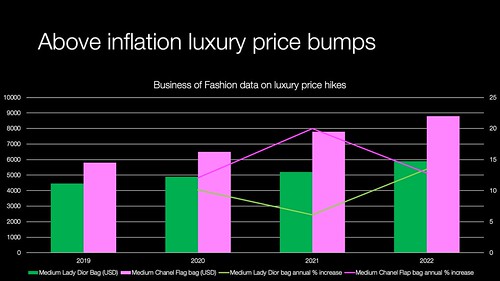

Luxury brands focused on their inflation proof ultra-high net worth customer base and raised prices to compensate for the reduction in sales volume. The fight for that reduced volume pitched multi-brand boutique e-tailers against their suppliers and the results weren’t pretty.

Boutique e-tailers are going to the wall, or consolidating to weather the fiscal storm until such time as middle class consumers can start spending aspirationally again.

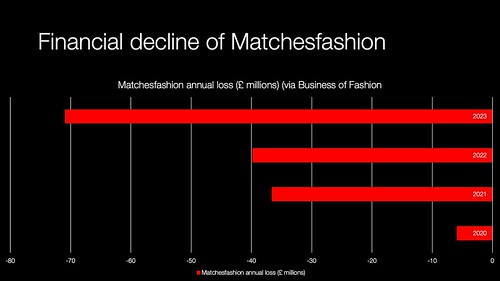

Some of these businesses can’t be saved. Matchesfashion, which was bought out by Frasers Group didn’t have much chance.

You can find similar posts here.

More information

The implosion in luxury ecommerce | FT

Case Study | Selling Luxury to the 1% | BoF

Matchesfashion axes half its staff after going into administration | FT

Harvey Nichols staff face redundancies as it eyes return to profitability – Retail Gazette

LVMH-Backed Luxury Watch Site Hodinkee Cuts a Fifth of Jobs – Bloomberg

Who Gets to Buy a Birkin Bag? | BoF

Canada Goose is cutting 17% of its corporate staff | Quartz

US Luxury Purchases Fell 15 Percent in February, According to Citi Credit Card Data | BoF