4 minutes estimated reading time

Brand Vandals preamble

Back in November 2012, my friend Wadds was researching and writing a book that would turn out to be Brand Vandals. I had a campaign going into mothers-and-babies screenings at cinemas and was in the final stages of preparing for a move to Hong Kong whilst launching an innovative facebook app for The National Lottery. The app featured a ‘scratch card’ mechanism within it, something I haven’t seen done since.

By this time Wadds and I had known each other for the best part of a decade and a half, having worked together on the 3Com (now part of HPE) and LSI Logic accounts at the start of my agency career in London.

Brand Vandals followed Wadds and Earl’s earlier book Brand Anarchy – the publishers were not enamoured with the original working title of Brand Fucked.

The Brand Vandals conversation.

The Brand Vandals conversation took place in The Stockpot in Panton Street. The Stockpot had a few branches in London was known for really cheap but good comfort food. Breakfast meant a fry up, which fitted in with our shared Northern sensibilities.

Wadds opened up with the question – had the social web failed to live up to initial expectations?

My reaction at the time was to point out the dissonance between social discourse and real life society. Twitter (or X) was where the bulk of political and media discussions happened, yet it was a small eco-system. Society in many respects hadn’t moved on from Roman times. While the intelligentsia might have had heated discussions in the forum (or on Twitter), these conversations didn’t reflect the vox populi. I name checked Juvenal, referencing Satire X ‘bread and circuses’ because it illustrated the two worlds neatly. The world of the political elites and the world of the common people with their different interests.

Ten years on, social channels have become much more ubiquitous. The early netizens who blogged and participated in forums and on Twitter have been joined by everyone else. The algorithms give people what they want, so political Twitter has its hecklers and fringe elements but still doesn’t reflect the voice of the people.

Facebook also had its fringe elements of discussion where the angry and paranoid could come together, rather like the USENET of old, but more accessible.

At the time, while I realised the digital inequalities that could be created by the data that consumers shared from the quantified self and telematics to the geolocation via their IP address. Tools in mining structured and unstructured data together with new devices putting telematics in the hand of everyone. All of that data was rip for (ab)use by corporates.

I don’t think that either of us fully realised how the world changes when it goes online.

In his book, Wadds quoted liberally from The Cluetrain Manifesto. What now could be seen to the last gasp of the libertarian bent of techno-hippy political thought. Doc Searls and David Weinberger’s book had more in common with The Whole Earth Catalog, The WeLL, John Perry Barlow and the back to the land counterculture movement than the modern web. Mark Zuckerberg et al represented the culture of Reagonomics rather than the ‘summer of love‘.

Scale has an effect of its own.

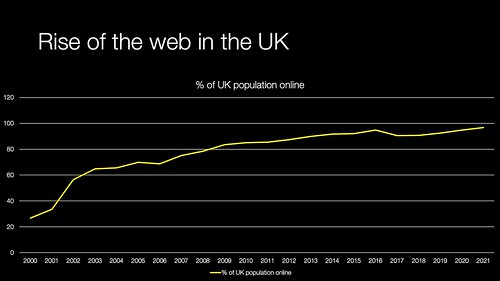

We didn’t fully realise what scale would do. Just like when social interactions and norms change when you go from a dinner party to an all-day music festival, the online rules changed. Looking back the scale is staggering, when you go from about a quarter of the UK population online during the dot com boom of 2000 to 88% online 12 years later. Between 2000 and 2002 the online population doubled in the UK. Part of this was driven the nascent mobile web, affordable internet service providers (giving a model more like the US) and adoption of broadband. Modern smartphones accelerated access further.

Hints of what could happen.

We had hints of the dark side through Chinese netizen culture and the phenomenon of human flesh search engine (人肉搜索) moral crusades, showing how people could come together in a common cause and be weaponised. This went back as far as the early 2000s. As far back as 2008, the Chinese judicial system was alarmed by its power and called it ‘cyber violence‘. It has been since turned loose on the wider world.

Joe Trippi, the political strategist behind Howard Dean’s campaign for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, showed how the web could be use to communicate, organise and fund raise back in 2004.

Information warfare found a febrile media that was ideal for its needs and was easy to scale operations on. It was no wonder in retrospect that the internet became toxic.

More information

Social web – people power? | renaissance chambara

Brand Vandals by Stephen Waddington and Steve Earl