15 minutes estimated reading time

What now for the working class?

What now for the working class? Following president Trump’s election and the British plebiscite on European Union membership there has been lots of hand wringing about workers who traditionally participated in legacy industries being outside society.

Here is what we have to deal with:

- The ‘traditional’ jobs aren’t coming back

- Middle-class roles are already being disrupted

- There is a declining return on investment in further education, yet lifelong learning is a compulsory requirement

- Globalisation is working at an aggregate level, but isn’t working at a local level

- Western society has fractured. It will become more fractious once the realisation takes hold that:

- It can’t be resolved by simple measures, populists might listen – but can’t solve anything. Jobs are governed by a multiple factors that affect both cost and demand considerations

- It can’t be solved in a relatively short time frame. You can’t build the necessary eco-system and supporting industries to bring the jobs back; even if the economics made sense

- Governments don’t have their hands on the levers of control, the best governments can do is actively manage decline. Technological disruption puts the levers of control with a smaller group of people

- There is a lack of willingness by those with the money and the power to solve it – primarily due to the pressures that drive their behaviour

- Existing social welfare safety nets aren’t sustainable

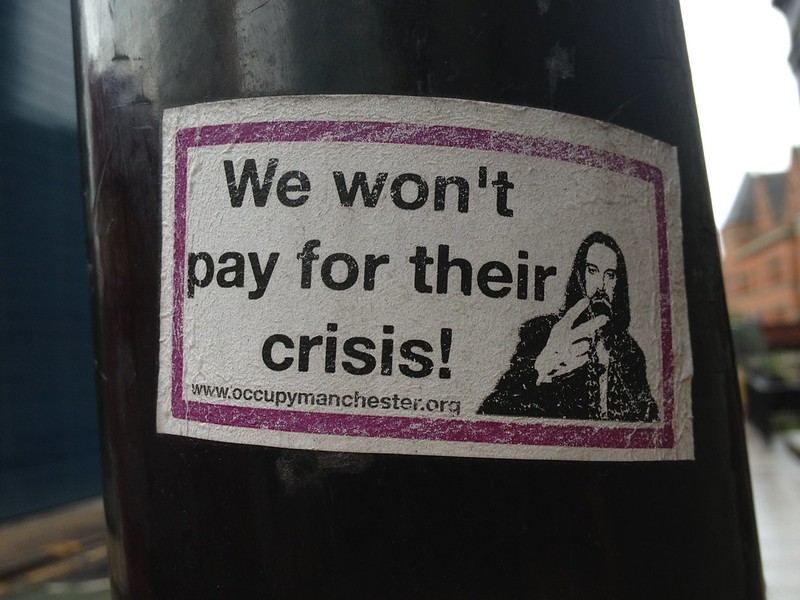

The realisation that populism doesn’t deliver is likely to cause a further visible outburst of anger. Which should be good news for the private security industry. This could result in civil or international conflict. It has already happened. Factors that contributed to the Arab spring and the Syrian civil war included a large under-employed population living in stagnant economic conditions with no hope in sight. This probably sounds familiar.

I am ruling out some sort of positive ‘black swan’ event which changes the game completely and provides meaningful work with great wages across societal boundaries. If I could reliably predict these, I would be writing this from my private Airbus A380.

Instead I can see four broad categories of outcomes, all of which are ugly:

- Carry on – carrying on isn’t likely to be sustainable as societal pressures go to breaking point

- Managed decline – from a rational point-of-view the most ‘possible’ solution. Unpalatable from a voter perspective. It begs the question at what point would the UK economy bottom out? Managed decline makes the most sense as an interim measure whilst a country works out what its new place in the world is and charts a path towards it based on careful strategic investments with limited capital

- Massive investment – presents a number of challenges that make it nearly impossible for western countries. It would require a long term view – unlikely without consensus driven politics with a high level of comity, huge access to credit – again unlikely with highly indebted economy and a slowly declining credit rating like the UK. Would take too long to satisfy angry voters

- Massive disruption – the dice is thrown in the air as society tears itself apart and the strong gain control – think China’s Cultural Revolution. Wages and worker rights may drop to make them more cost competitive for low skilled manufacturing allowing for an employed but disgruntled workforce. Power is unlikely to shift too much, the corresponding upheaval in population numbers may provide some supply side pressure on wages when its all over. In all likelihood, it would just reduce pressure for change, increased willingness to work together on a longer term solution, but not provide much medium term economic benefit

Disruption

Here is a chart of numerous successful business, some of them are over a century old. AT&T and Verizon can trace their history back to 1877 and the Bell Telephone Company set up by Alexander Graham Bell’s father-in-law. General Electric goes back to work by Thomas Edison in 1880. These companies took from 117 – 137 years to become $200 billion businesses. Facebook took ten years requiring only 3% of the people AT&T needed.

It would be reasonable to assume that the future is going to create less jobs with given investments rather than more.

| Company | #Employees | Year its market capitalisation became US$200 billion |

| 9,199 | 2014 | |

| Microsoft | 27,000 | 1998 |

| Apple | 46,600 | 2010 |

| Alphabet (Google) | 46,600 | 2012 |

| Amazon | 165,000 | 2015 |

| Verizon | 176,800 | 2014 |

| General Electric | 239,000 | 1997 |

| AT&T | 302,000 | 2007 |

So large private enterprises will:

- Employ less people which means less ancillary demand for services in the locale. Less restaurants, shops, artisanal coffee shops, micro breweries, nail bars, car valets, hotels and hair salons

- Employ even less unskilled people – what unskilled labour is required will be employed on a flexible basis. Their roles will be competing on ‘total price’ with a global workforce and robotics

This hypothesis is supported by data from the MIT Technology review which showed that modern US manufacturing managed to increase productivity by 250% whilst reducing staff numbers by over 40%.

Win-Win to Winner Takes All

Technological progress and globalisation has resulted in a decline in the middle class in western countries. Pew Research claims that the US middle class declined from 61 per cent of the population in 1970 to 50 per cent by 2015.

Corresponding average ‘real wages’ for US ‘good producing’ workers peaked by the mid-1970s and have been broadly stagnant since. A pattern mirrored in other developed economies. Hong Kong saw a similar peak from 1967 riots through to the early 1990s until factories moved across the border.

Manufacturing productivity had grown steadily over that time. You can argue over the data points but the overall trend seems to hold true.

Owners of capital have enjoyed increased returns versus the providers of labour. Knowledge work, a key part of middle class roles could be easier to export than production lines. A classic example is the bank back office roles that have been exported to India.

Supply chain

At the moment UK manufacturing jobs operate as part of a complex supply chain that primarily addresses the European Union as a market. The supply chain is built around a number of factors:

- The value of the product

- The weight of the product

- The volume of the product

- The cost of shipping versus the cost of production

- How well the product travels

- Distribution of product demand

- Proximity to suppliers

- Proximity to talent

This is why companies may package a product in one country and manufacturer in others. Washing powder is a classic example of this. Chocolate travels well, so Cadbury could move production lines of internationally popular products to Poland. There is a greater incentive to move low skilled work out of areas that aren’t geographically central to a given supply chain. European freedom of movement may have kept jobs in the UK by allowing low and semi-skilled workers to move rather than the factories. This would be of little consolation to UK workers, but would benefit UK tax coffers.

This complex formula is the reason why jobs move in and out of the UK.

Cutting the UK out of this supply chain with a hard Brexit ensures that suppliers have to make complex choices. BMW will probably be wondering what UK presence it needs to maintain in order to keep the Mini brand values. It may decide its easier to evolve the quirky Britishness out of the brand over time and just keep it quirky. The Audi TT hasn’t been harmed by actually being assembled in Hungary.

The majority of components in the supply chain for the Mini production line is based in Germany.

A post-Brexit UK could be in the position of importing more rather than less products once companies take into account the bigger picture of the supply chains and the EU single market. This will lead to a net loss of working class livelihoods.

Role of eco-systems

Richard Florida is a Canadian professor who has spent much of his time looking at urban studies from the perspective of prosperity. He is known for is work around the creative class and urban regeneration (or gentrification). His work is controversial. One key concept he has of relevance to working-class communities is one of ‘clusters’ where eco-systems exist. When you apply it to traditional working class industries one can see how the jobs aren’t just going to come back. The UK has a series of traditional clusters that are in overall decline, this is best illustrated by the state of chemical, oil refinery and coal sectors which underpin a wide range of manufacturing industries.

Where new clusters spring up (Silicon Roundabout and the FinTech businesses within the Square Mile) they create employment that much of the UK population is ill-equipped to fulfil.

Let’s look in greater depth at traditional manufacturing industries that have provided the working class with good playing jobs.

Factories build on suppliers, who build on raw materials processors, who build on utilities and extractive industries. Take for example industrial revolution era Stoke-on-Trent which was close to high quality clay pits and coal that could be cheaply shipped in from mines in Lancashire or South Yorkshire. All of which required semi-skilled and unskilled jobs that gave the working class their livelihoods.

Unfortunately for Stoke-on-Trent; clay is readily available around the world, opening up the possibility of production in areas with cheap labour. Automation raised the quality of production and fashion can quickly dictate whether an ‘area’ brand is in demand.

If we look at the industrial landscape of the United Kingdom, the manufacturing industry has been hollowed away during the 1980s and 1990s. The UK lost 18% of its manufacturing capacity in the space of 18 months during the conservative government of Margaret Thatcher.

There has been a corresponding (likely terminal) decline in the necessary facilities to support an industrial economy. Now let’s look in-depth at three essential types of facilities that underpin manufacturing:

- Oil refineries

- Coal mines

- Chemical plants

This base of the UK industrial eco-system is running on ‘life support’ in critical areas.

I was fortunate to have a great science teacher at school, he once said to me that you could measure the size and health of an industrial economy by the amount of sulphuric and hydrochloric acid it manufactured and consumed. In order to manufacture hydrochloric acid you need a chlorine gas plant – neither chemical is something you want to transport over long distances. The side effects of a leak would be catastrophic.

The UK currently has one plant to make chlorine gas that is government subsidised because there isn’t a sufficiently large industrial base to support continued profitable production. What industrial capacity is in the UK is perilously close to being snuffed out.

What is left of the UK chemical industry has consolidated in the North East of England Process Industry Cluster (NEEPIC). Some of the products created are intermediary chemicals for use elsewhere in the European Union. Brexit is likely to have a disruptive effect on some of these manufacturers. The cluster is a key reason why Nissan decided to build a manufacturing plant in Sunderland. NEEPIC is dependent on oil refining capacity for key chemical building blocks (feedstock).

Oil refineries

Oil refineries are considered by the public as providers of petrol (gasoline), diesel and jet fuel. The reality is that they provide feedstock (chemical building blocks) for most things in everyday life:

- Foods

- Medicines (or we can go back to leeches and blood letting)

- Paints (containers, large manufactured goods, civil engineering)

- Dyes to colour fabrics, plastics and other materials

- Plastics (the modern world as we know it) – structural plastics, coatings, fibres including clothing textiles

As I write this is, it is easier to look around my desk and count the products that don’t have an oil-derived input – one item, the desk itself which is unpainted. Though I would put good money on it that the trees it was made from were felled with petrol chain saw and transported on a diesel-powered lorry to the saw mill.

Yet the UK has lost a huge amount of oil refining capacity. From 1974 – 2012 refining capacity almost halved from 148 million tonnes to 77 million tonnes (Energy Institute). This decline happened despite start of UK North sea oil production in 1975.

Peak production on North Sea oil occurring in 1985 and 1999 (two peaks due to technological innovation). There were 22 active oil refineries in 1974, at the time of writing there are now seven.

Part of this was driven by changing energy consumption such as the decline of home heating oil and more fuel efficient cars. But a good deal would be due to reduced ability to compete against foreign petro-chemical feedstocks and reduced industrial capacity.

Oil refining capacity has moved to closer to where the industry is.

Belgium and the Netherlands have oil refining capacity beyond their internal needs because of their ease of access to continental European markets. Germany as Europe’s industrial powerhouse has the largest refining capacity in the European Union – which matches its industrial economy.

Much of the capacity to provide chemical feedstocks for industrial use has moved to the Far East; notably Singapore, Japan, Korea, Jamnagar in India and China. Overall industrial production has moved to East and Southeast Asia.

Coal production

The working class found coal production as a source of working class jobs. Even coal production in the UK is roughly 10 percent of what it was in 1980. There are no deep coal mines active in the UK, only a handful of open cast mines. Coal is not only useful as a fuel but also a alternative supplier of feedstock for a diverse range of products including fertilisers, plastics and medicines. Even if coal comes back to prominence as oil reserves run out it would take a lot of effort to get UK production going again – perhaps too much effort.

Managed decline of traditional working class areas

The purpose of managed decline would be to concentrate efforts where they can make the most impact. London would draw in more people from the hinterlands. Cities like Liverpool would continue to decline in population. Low quality housing (think trailer parks or shanty towns) would cater for the internally displaced workers and there would be a likely increase in casual or gig economy roles in place of many working class roles.

So what would managed decline of working class areas look like? We have a clue from government discussions after the 1981 Toxteth riots. Lord Geoffrey Howe wrote a letter which was considered too controversial at the time

“I fear that Merseyside is going to be much the hardest nut to crack,”

“We do not want to find ourselves concentrating all the limited cash that may have to be made available into Liverpool and having nothing left for possibly more promising areas such as the West Midlands or, even, the North East.

“It would be even more regrettable if some of the brighter ideas for renewing economic activity were to be sown only on relatively stony ground on the banks of the Mersey.”

“I cannot help feeling that the option of managed decline is one which we should not forget altogether. We must not expend all our limited resources in trying to make water flow uphill.”

Howe realised that even discussing the concept at the time would be explosive.

Retrenchment to focus economically

In practical terms, it would mean:

- Re-centralising government departments

- Not spending on infrastructure beyond critical maintenance

- Rationalising government support infrastructure: police, hospitals, social services

- Re-zoning areas from a planning perspective to encourage development only in future clusters

- Allowing local government to go into bankruptcy protection and under go US-style emergency management

- Once population decline hits a critical mass, turning off the last services, rather like the city of Detroit has done

- Focus infrastructure investment on ‘clusters’

- Connecting benefits to re-location

This process would then give time for western countries; in particular the UK, to re-invent themselves and think about their economic purpose in the world beyond consumption.

The Chinese government have already started on this process whilst their economy is still in a high state of growth – looking to move up the manufacturing value chain, moving into the professional and financial services sectors that the west currently occupy. On the flip side they have not flinched from closing down excess capacity in the steel industry and low value industries. This is causing economic hardship amongst unskilled workers in Guongzhou and the steel towns of Hubei province.

Former clothing factories are being bulldozed to make way for corporate campuses. Small electronics factories in Shenzhen are making way for a financial services centre including a stock exchange.

If one thinks about the Chinese experience and their migration to higher value work, where would the UK go next and what does mean for the future of the British working class?