9 minutes estimated reading time

The web as we know it was built on a set of underlying technologies which enable information transport. Not all information is meant to reside in a website to be surfed or queried. Instead much of the information we need relies on context like location, weather or the contents of your fridge. Web technologies provided an lingua franca for these contextual settings and like most technological changes had been a long time in coming.

You could probably trace their origins back to the mid-1990s or earlier, for instance the Weather Underground published Blue Skies; a gopher-based graphical client to run on the Mac for the online weather service back in 1995. At this time Apple were working on a way of syndicating content called MCF (Meta Content Framework) which was used in an early web application called Hot Sauce.

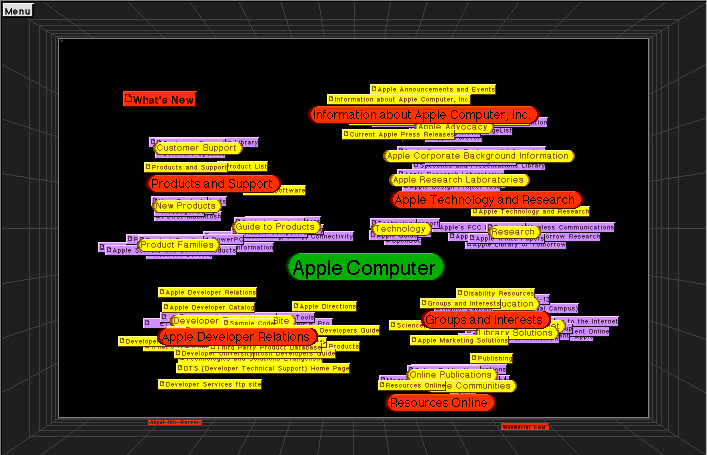

Hot Sauce was a web application that tendered a website’s site map in a crude 3D representation.

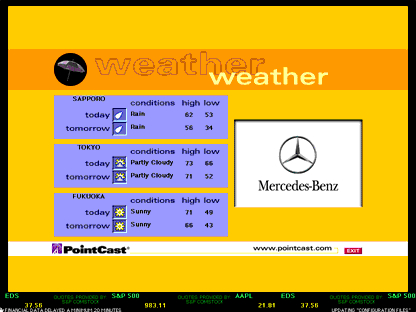

A year later PointCast launched its first product which pushed real-time news from a variety of publications to a screen saver that ran on a desktop computer.

The key thing about PointCast was it’s push technology, covered in this edition of the Computer Chronicles

The same year that PointCast launched saw the launch of the XML standard: markup language that defines a set of rules for encoding documents in a format that is both human-readable and machine-readable. This meant that there was a template to provide documents and stream information over the web.

Some of the Apple team responsible for MCF had moved to Netscape and worked on ways of importing content from various media outlets into the my.netscape.com portal; they created the first version of RSS (then called RDF) in 1999. The same year, Darcy DiNucci coined the term web 2.0; whilst this is associated with the rise of social networks, it is as much about the knitting of websites: the provision of services online, integration between websites taking data from one source and melding it with another using a web API formatted in an XML type format or JSON – which does the same job.

By the early noughties applications like Konfabulator (later Yahoo! Widgets) launched their first application to ‘put a skin on any information that you want’.

Major web properties started to license their content through APIs, one of the critical ideas that Flickr popularised was that attribution of the data source had its own value in content licensing. It was was happy to share photos hosted on the service for widgets and gizmos so long as users could go back through the content to the Flickr site. This ability to monetise attribution is the reason why you have Google Maps on the smartphone.

So you had data that could be useful and the mechanism to provide it in real time. What it didn’t have so far was contextual data to shape that stream and a way of interfacing with the real world. In parallel to what was being driven out of the US on the web, was mobile development in Europe and Asia. It is hard to understand now, but SMS based services and ringtones delivered over-the-air to handsets were the big consumer digital businesses of their day. Jamba! and their Crazy Frog character were consumer household names in the mid noughties. It was in Europe were a number of the ingredients for the next stages were being created in meaningful consumer products. The first smartphones had been created more as phones with PDAs attached and quicker networks speeds allowed them to be more than glorified personal information managers.

The first phone that pulled all the requisite ingredients together was Nokia’s N95 in early 2007, it had:

- A good enough camera that could interact with QRcodes and other things in the real world

- Powerful enough hardware to run complex software applications and interact with server-side applications

- A small but legible colour screen

- 3G and wi-fi chipsets which was important because 3G networks weren’t that great (they still arent) and a minimum amount of data network performance is required

- A built-in GPS unit, so the phone ‘knew’ where it was. Where you are allows for a lot of contextual information to be overlaid for the consumer: weather, interesting things nearby, sales offers at local stores etc

All of these ingredients had been available separately in other phones, but they had never been put together before in a well-designed package. Nokia sold over 10 million N95s in the space of a year. Unfortunately for Nokia, Apple came out with the iPhone the following autumn and changed the game.

It is a matter of debate, but the computing power inside the original iPhone was broadly comparable to having a 1998 vintage desktop PC with a decent graphics card in the palm of your hand. These two devices set the tone for mobile computing moving forwards; MEMs like accelerometers and GPS units gave mobile devices context about their immediate surroundings: location, direction, speed. And the large touch screen provided the canvas for applications.

Locative media was something that was talked about publicly since 2004 by companies like Nokia, at first it was done using laptops and GPS units, its history in art and media circles goes back further; for instance Kate Armstrong’s essay Data and Narrative: Location Aware Fiction was published on October 31, 2003 presumably as a result of considerable prior debate. By 2007 William Gibson’s novel Spook Country explored the idea that cyberspace was everting: it was being integrated into the real-world rather than separate from it, and that cyberspace had become an indistinguishable element of our physical space.

As all of these things were happening around me I was asked to speak with digital marketers in Spain about the future of digital at the end of 2008 when I was thinking about all these things. Charlene Li had described social networks as becoming like air in terms of their pervasive nature and was echoed in her book Groundswell.

Looking back on it, I am sure that Li’s quote partly inspired me to look to Bruce Lee when thinking about the future of digital, in particular his quote on water got me thinking about the kind of contextual data that we’ve discussed in this post:

Don’t get set into one form, adapt it and build your own, and let it grow, be like water. Empty your mind, be formless, shapeless — like water. Now you put water in a cup, it becomes the cup; You put water into a bottle it becomes the bottle; You put it in a teapot it becomes the teapot. Now water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.

Lee wrote these words about his martial arts for a TV series called Longstreet where he played Li Tsung – a martial arts instructor to the main character. Inspired by this I talked about the web-of-no-web inspired by Lee’s Jeet Kune Do of ‘using no way as way‘.

In the the slide I highlighted the then new points of interaction between web technologies and platforms with the real world including smartphones, Twitter’s real-world meet-ups, the Wii-controller and QRcodes.

A big part of that context was around location aware applications for instance:

- Foursquare-esque bar and shop recommendations

- Parcel tracking

- Location based special offers

- Pay-per-mile car insurance

- Congestion charging

- Location-based social networking (or real-world avoidance a la Incognito)

- Mobile phone tour guides

And that was all things being done six years ago, with more data sets being integrated the possibilities and societal implications become much bigger. A utopian vision of this world was portrayed in Wired magazine’s Welcome To The Programmable World; where real-world things like getting your regular coffee order ready happen as if by magic, in reality triggered by smartphone-like devices interacting with the coffee shop’s online systems, overlaid with mapping data, information on distances and walking or travel times and algorithms.

What hasn’t been done too well so far has been the interface to the human. Touch screen smartphones have been useful but there are limitations to the pictures under glass metaphor. Whilst wearable computing has been experimented with since the early 1970s and helped in the development of military HUDs (head-up diplays) and interactive voice systems, it hasn’t been that successful in terms of providing a compelling experience. The reasons for this are many fold:

- Battery technology lags semiconductor technology; Google Glass lasts about 45 minutes

- The owner needs to be mindful of the device: smartphone users worry about the screen, Nike Fuelband wearers have to remember to take them off before going and having a swim or a shower

- Designs haven’t considered social factors adequately; devices like Google Glass are best matched for providing ‘sneak information’ just-in-time snippets unobtrusively, yet users disengage eye contact interrupting social interaction. Secondly Google device doubles as a surveillance device antagonising other people

- Many of the applications don’t play to the devices strengths or aren’t worth the hassle of using the device – they lack utility and merit

That doesn’t mean that they won’t be a category killer wearable device or application but that they haven’t been put on the market yet.

More information

Fragmented Future – Darcy DiNucci

Data and Narrative: Location Aware Fiction – trAce

William Gibson Hates Futurists – The Tyee

The future of social networks: Social networks will be like air | Empowered (Forrester Research)

Groundswell: Winning in a World Transformed by Social Technologies by Charlene Li and Josh Bernoff

Welcome To The Programmable World | Wired

A brief rant on the Future of Interaction Design | Brett Victor

The Google Glass post | renaissance chambara

I like: Sony’s Smarteyglasses | renaissance chambara

The future of Human Computer Interaction | renaissance chambara

Consumer behaviour in the matrix | renaissance chambara

Eight trends for the future

Eight trends for the future: digital interruption

Eight trends: Immersive as well as interactive experiences

Eight trends for the future: Social hygiene

Eight trends for the future: contextual technology

Eight trends for the future: Brands as online tribes

Eight trends for the future | Divergence

Eight trends for the future: Prosumption realised