5 minutes estimated reading time

Working as a remote team got me thinking about playlists and mixtapes. One of my colleagues started off a themed playlist on Spotify. The playlist creativity was based around a narrative. The narrative is driven by song title.

Spotify made it easy to collaborate on putting more in there.

Its a form of surface data, easy to see. Easy for machines to grasp.

It is easy to analyse. Hence Spotify’s ad campaigns and pitch to advertisers based on data.

Initially, I thought it was this data treasure trove that made me feel uneasy about music streaming services. Where other people felt Spotify’s ads were clever, I felt they were intrusive, even voyeuristic. It felt voyeuristic reading some of them.

Music curation is a very personal thing. But in the end I realised it wasn’t the data that bothered me. Now I realise its the nature of curation and consumption on the platforms.

Music is something that exists in everyone’s lives. For some people it was background wallpaper. It occasionally took on ‘sound track’ starring roles at important life moments. For instance, the track the bride and groom choose to dance to at their wedding. Or a one-hit wonder attached to holiday nightlife memories.

For some people it moves beyond being a trigger. It stirs a passion. Myself and some friends have collections of records. Owning a thing has a power of its own. Digital services don’t really understand this drive.

iTunes organisation

iTunes in its day revolutionised digital music. It made music accessible in way that consumers wanted. But it wasn’t a perfect experience.

For instance, someone like myself won’t necessarily follow an artist. Electronic music often sees artists change names as often as changing an overcoat.

The producer or remixer becomes important. Tom Moulton back in the days of disco, Danny Krivit’s famous edits or London’s Nicolas Laugier (The Reflex). All of them have distinctive sounds that bring tracks to life.

A record label becomes synonymous with a particular sound. Blue Note Records’ jazz, Strictly Rhythm’s New York tinged house music or the early rock of Sun Records. This is a mix of a curators ear, in house studios, producers and engineers.

Yet in iTunes you could never search by remixer, or record label in the way that you could search for an artist or group name.

Even the way iTunes treated DJ names indicated a lack of understanding. Someone like myself would treat DJ, the way rock fans would treat ‘The’ in a band name. So DJ Aladdin would come before The Beatles. But DJ Krush would come after.

In iTunes, it ignores ‘The’ so The Beatles sit just behind The Beastie Boys. Both of them come before DJ Aladdin who is grouped with with all the other DJ names.

Playlists and mixtapes

iTunes introduced the concept of playlists with the iPod, but the marketing around it was creating lists for how they made you feel. Music to run by, a chillout list etc.

In design, this was closer to a mixtape than a typical Spotify playlist. Apple worked on making them social. At one stage artists could share playlists of tracks that influenced them. Apple tried to create editorial content around it. It was an interesting idea, but discovery in iTunes was problematic.

A mixtape is about careful curation. You take the listener on a journey, it is often meant to convey a feeling or an emotion. One of the few people that I’ve seen do this within Spotify has been Jed Hallam’s Love Will Save The Day selections. A non-verbal message.

A mixtape was often time bounded by its medium.

- Cutting your own vinyl record which was done on 78rpm discs might give you 2 minutes. Enough for a short voice mail home, if the record survived the postal system.

- Reel to reel tape might give you up to 90 minutes at reasonable quality on a 10 1/2 inch reel of tape.

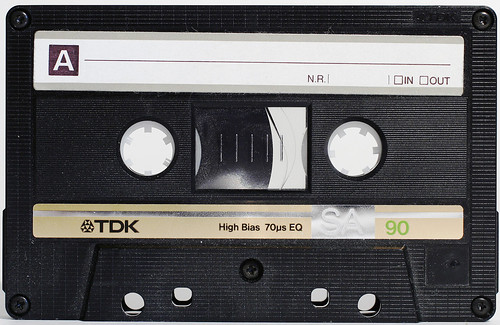

- Cassette tapes were typically 30 or 45 minutes per side.

- CDs could provide up to 80 minutes, depending on the disc. But the original ‘Red Book’ standard capacity was 74 minutes

The playlist has no capacity considerations. No limitations that force choices or prioritisation.

Consuming playlists and mixtapes

A mixtape often brought a deeper experience to the listener. Whether it was an expression of love, passion or nerdiness. A playlist tends to operate much more at a surface level. This changes the dynamics of consumption. A playlist doesn’t require active listening. Its like drive-time radio. A backdrop to life.

A playlist is often found, again rather like tuning into a radio station. It is usually a more passive consumption experience. The audience has less invested in it.

Playlists and mixtapes business models

This difference in attitude helps explains how music changed in fundamentally in business model. When you’re more passive, you don’t need to own your music.

You don’t mind if tracks disappear due to licencing disputes. Music becomes a utility that you pay for each month. In this respect Spotify looks a lot like the post-war Rediffusion service.

It’s an operating expense rather than a capital outlay for young consumers. It facilitates algorithm as taste maker which leads to a reductive path. Apple Music has tried to keep away from this. They’ve got specialist curators in niche genres. Want to hear the best of bluegrass and outlaw country? Apple Music likely covers you better than Spotify.

If I am following your playlist, it opens up opportunities for payola. Artist brands become less important than a steady stream of releases in popular genres. Music plugging becomes an arbitrage play; streams versus promotional costs RoI. Traditional artist development no longer makes sense. Instead you end up with a model that looks closer to a fast-failure production line. More on media related topics here.