13 minutes estimated reading time

I was reading Rob Manuel’s Facebook post about the origin of B3ta’s ‘magic donkey’ and its wider connection to the modern dystopian web experience.

B3ta and magic donkey

I guess it makes sense to first explain what B3ta is. B3ta is a community of bored driven people with a creative bent and a finely tuned sense of the absurd. The Guardian described it as a ‘purile digital arts community’. To be fair the works are more multi-displinary, than just digital in nature. Brands and memes get hacked.

Its humour and its contributors are mostly British.

B3ta was founded as a website and forum back in 2001 and I found it as a passive consumer a few years later. The front page and weekly email sent to members curated a selection of the content in the forums. Whilst contributors weren’t paid, there was a lot of kudos to getting your content on to the front page of the website, or into the weekly email that went out to the community of creators and consumers.

This meant that Manuel was under pressure by contributors to put their work on the front page or in the weekly update email. The ego of the creator is familiar to anyone who has watched TV shows or films such as:

Manuel invented an imaginary editor to deflect pressure away from himself. Of course, imaginary editor had to be slightly absurd. Hence a magic donkey.

Flickr and the magic donkey

While Rob Manuel was responsible for trying to fend off B3ta contributors aspirations to get on the front page, Cal Henderson was responsible for the technology. He had been a co-founder of B3ta alongside Manuel.

Henderson is better known as a long time collaborator with Stewart Butterfield and CTO of Slack. But before that he was responsible for the technical aspects of B3ta and then moved on to Flickr.

Flickr had a strong tight community, with agreed well-adhered to rules. A large part of this was down to the Flickr team including co-founder Caterina Fake and Heather Powazek Champ. The community met up in real life; rather like users of Chinese network Douban had been known to do. Flickr users were also good at organising their pictures providing labels or tags for images. But as the community scaled, surfacing the right content at the right time would have been more difficult.

Henderson word on a algorithm-driven function called ‘interestingness’ that surfaced ‘the best’ content on a particular subject. Here’s what Steve’s Digicams said about is likely to go into the ‘Interestingness’ algorithm.

There are a number of factors that go into what makes a photo interesting including, the number of tags it has, the number of groups it belongs to, how many people have viewed the image, and how many people have made it their favorite.

Steve’s Digicms – What is Flickr Interestingness?

Cal Henderson called the algorithm ‘magic donkey’. This would be a substitute for the curation done by an editor or a community manager and be applied across all subject areas. If the descriptions of Henderson’s interestingness algorithm reminds you a bit of Larry Page and Sergei Brin’s original working paper The PageRank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web, you’re probably right. At a base level both seem to rely on different feedback mechanisms to provide a reductive way of resolving what to show. Feedback as a concept is a hugely important role in computing and technology. Bell Labs were using feedback in its solutions to reduce noise on telephone lines at the start of the modern electronic age. Now feedback and analysis is done thousands of time a second to try and provide robots with some form of situational awareness.

Magic donkey, search and social search

Just over 12 months after it was formed, Flickr was purchased by Yahoo!. Yahoo! was interested in flickr for a number of reasons:

- Yahoo! (and Microsoft) were fighting a losing battle against Google’s search engine and needed an edge

- Web 2.0 had started to take off and Flickr was a cool property in this space.

At that time search lacked meaning and context. To help you understand what search was like back then. I used to use the analogy of a shop assistant

Imagine going to the supermarket and asking the assistant for an item, they run down the corridor and run back with their arms full of different stuff. They empty the stuff into your trolley and say to you ‘Your item is in there’. If you are lucky, the item is at the top of the pile, it you aren’t you may sort through it all and find you don’t have it anyway. You complain to the manager and he dismisses you with ‘Its your own fault, you asked in the wrong way’.

Folksonomy.

In order to deal with the meaning and context problem, all the main search engines brought out vertical search services

- Video Search

- Maps

- Blog search

- Google Scholar

- Shopping search

And ‘easter eggs’ such as providing information on local time in different cities or countries and measurement conversions. Whilst these weren’t great at driving advertising revenue they encouraged usage. Search became a giant Swiss army knife for knowledge workers.

All the search providers had a keen interest to the GWAP (games with a purpose) work that was being done at Carnegie Mellon University by Luis von Ahn. von Ahn is a specialist in the field of ‘human computation’.

Human computation was providing machine learning something to learn from. You want to teach a machine learning algorithm how to identify cats? von Ahn’s ESP game was the ideal teacher. In the words of von Ahn’s own page at Carnegie Mellon University:

The first GWAP developed by von Ahn, the ESP Game displays images to two players who each try to guess words that the other player would use to describe the image. The game improves web image searches by generating descriptions of uncaptioned images. Google Inc. has licensed the game, which the company calls Google Image Labeler.

Games With A Purpose – Carnegie Mellon University

von Ahn went on to design other games that would have a similar utility

- Matchin, a game in which players judge which of two images is the more appealing. (This might introduce cultural bias and would probably be much more problematic now.) Back in the late noughties this was seen as progress towards better search. Automating systemic racial bias just wasn’t on the radar and ‘bro culture’ wasn’t as prevalent in its engineers

- Tag a tune – which looked to get genres and descriptors like happy or sad music

- Verbosity – tests ‘common sense’ knowledge to build facts for machine learning platforms like ‘you shouldn’t walk under ladders’

You can still try Google’s use of GWAP here. Though most people are more used to engaging with GWAP functions as part of CAPTCHA and reCAPTCHA verification services. Google used reCAPTCHA and CAPTCHA technology to digitise the archives of The New York Times and libraries into Google Books.

Yahoo!’s answer to this has been variously termed knowledge search and social search. The idea was to improve the quality of results through people and provide context through human effort. A few of the things were in Yahoo!’s favour for this approach.

Heuristics that support social search

Search like many categories of commerce, tends to follow the principle of the long tail. The bulk of interest or transactions are the head. This existed pre-Internet; if you’re of a certain age you’ll remember that most people seemed to have a Sade or Dire Straits album in their CD collection. Ed Sheeran or Beyonce on their Spotify playlists would be a similar phenomenon now.

Search is quite similar. The biggest searches on search engines are likely to be something along the lines of:

- Porn

- Google (on Yahoo! or Bing)

- Amazon

- eBay

(The lists that you see published of the top searches put out by Google, Yahoo! etc are usually cleaned first by the PR teams; so have limited value as trustworthy information sources.)

A lot of searches are looking for things that you’ve found before online. Whether it was a particular article or a website that you use on a regular basis.

Social search was manifested in a number of different ways. Questions and answer sites had originally got popular in east Asia, notably Korea, Taiwan and Japan.

Jerry Yang himself got behind the launch of what would become Yahoo! Answers following the popularity of a Q+A service launched by Yahoo! in Taiwan.

Yahoo! had an interest in tagging and folksonomies as a way of providing context around content. In a similar way to the way lexemes work.

So if you were listening to a report on the stock market. The report wouldn’t necessarily have to use the phrase stock market to indicate that was what the report was about. There would be lexemes – words associated with the concept of a stock market that would be indicators for instance:

- Wall Street

- Bull market

- Bear market

- Standard & Poors 500 (S+P500)

- NASDAQ

- Share price

- FTSE

- The Hang Seng

- The Nikkei

There would be similar language for other subjects as well. This allows for one item to be in multiple categories. Yahoo! acquired Flickr which helped because it had a community that tagged their images.

Yahoo! also launched a series of social bookmarking services. Remember what I said earlier about people often searching for things that they’d found before? Well a social bookmarking tool offers a few benefits

- Your bookmarks exist online so you don’t have to worry about getting access to your browser bookmark folder at home, at work or on the move

- You organise things using the language that makes the most sense for you

- You can search amongst links that you’ve found before

- Searching amongst content that you and others like you chose to bookmark should raise the overall quality of the links that you are provided with

There was Yahoo! MyWeb, MyWeb 2 (beta) and it then acquired Delicious. Stewart Butterfield used to joke that Yahoo! bought flickr because they thought flickr were the ‘tagging people’; when they’d really just been copying the feature from Joshua Schacter at Delicious. Yahoo! then went on to buy social bookmarking site Delicious as well.

The problem is that to tag your bookmarks and content carefully requires a discipline that many people struggled to maintain. I have found it to be personally beneficial over time, but I had a strong incentive to stick with it; even then I have been far more lax on my photo tagging since I no longer use Flickr’s desktop app to upload my photos.

Changing behaviour is hard; when I worked there, reputedly a higher proportion of Yahoos used Google search than the general population. I heard that there was a similar behaviour pattern at Microsoft.

There is also a certain irony in Henderson et al falling back closer towards a Google PageRank citation / feedback-type model of algorithm given the nature of a more human-powered and humane ideal of social search.

Magic donkey and content firehose

Cal Henderson literally wrote the book on scaling websites to cope with the kind of growth you would see driven by social web applications such as photo sharing, bookmarking and social networks.

But social networks grew at a phenomenally fast rate. You could never log on to Friendster. That meant that the bar was set very low for MySpace to compete against Friendster.

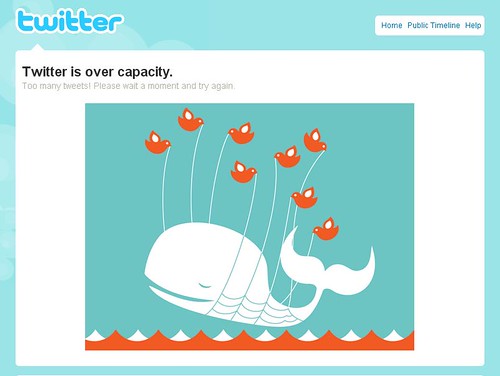

MySpace and Facebook were initially very sluggish sites. Twitter and the ‘fail whale’ of the site being down were a cultural touchstone of the late noughties.

This increase in audience, meant a consequent increase in content. YouTube for example was running at over 45minutes of video being uploaded every minute. I am sure that rate is even greater now. How to sort through this firehose of content?

To engineers the solution would look a lot like Henderson’s magic donkey. Algorithms slowed down the newsfeed to something more manageable, otherwise it would overwhelm the users.

On the commercial side, the social platforms need to show sticky content that will keep users on their site longer and that they can vend advertising against.

No great plot to up-end civilisation or spread hatred and bile. But algorithms can have unintended consequences. Content that polarises, engages. The algorithm doesn’t know that’s a bad thing. Soon those that want to engage with audiences in an emotive political way understand how the system can work with them.

A mix of trial and error with a bit of understanding of behavioural science and continual learning allows political actors to learn how to use the system. Incremental tweaks in approach that their rivals or peers make drives that knowledge at a faster rate than the algorithms seem to evolve. The algorithm is blind to it all. It sees the things it cares about ‘improving’. Time spent on service, engagement with content, commenting and sharing. A human-machine feedback mechanism is created.

In essence, it’s Google’s ‘stupid shop assistant’ all over again and this time human input in the feedback mechanisms is hurting rather than helping the magic donkey of social platforms.

More on flickr here and more on internet culture here.

UPDATE (September 24, 2020): Earlier this week the FT ran the story ‘YouTube reverts to human moderators in the fight against misinformation‘ – in an apparent indication that the ‘magic donkey’ model has reached its limits (at the moment). YouTube’s machine learning algorithms when given control had a false positive bias banning a ‘significant number’ of videos that broke no rules. In a three month period 11 million videos were taken down. (The usual number is about half that).